Chapter 6: The Long March through the Institutions

Chapter 6: The Long March through the Institutions

This chapter, in my opinion, is the most important chapter in the book.

It details how we have got ot where we are today, a deeply divided society, where one side, steeped in cultural Marxism and displaying a sense of moral superiority, hurls abuse at the other side, accusing it of racism, homophobia, Islamophobia, white supremacy and a host of other evils.

Author of The Long March: How the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s Changed America, Roger Kimball writes:

Although sometimes tempted to ignore it, we are living in the aftermath of a momentous social and moral assault.[i]

David Frum observes in How We Got Here, his book about the 1970s, that Americans are the heirs of “the most total social transformation that the United States has lived through since the coming of industrialism, a transformation (a revolution!) that has not ended yet.”[ii]

In 1991, looking back over his long and distinguished career in an essay called a “Life of

Learning,” the philosopher Paul Oskar Kristeller sounded a similar melancholy note:

We have witnessed what amounts to a cultural revolution, comparable to the one in China if not worse, and whereas the Chinese have to some extent overcome their cultural revolution, I see many signs that ours is getting worse all the time, and no indication that it will be overcome in the foreseeable future.[iii]

What was this cultural revolution and how did it come about?

How cultural Marxism came to dominate Western culture

Cultural Marxism, dubbed “the greatest cancer in the Western world,” is the ideological driver behind political correctness. It is the destructive criticism and undermining of all the institutions of Western civilization and the traditional values underpinning it.

Cultural Marxism was formulated as a way to subvert Western nations and civilization using methods other than direct political action.

Cultural Marxism is largely a synthesis of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. It is Marxism as applied in the cultural sphere and the analysis and control of the media, art, theatre, film and other cultural institutions in society, often with an emphasis on class, race and gender.

Shortly after the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in the October Revolution of 1917, they founded the Comintern (Communist International) to “fight by all available means … for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie for the creation of an international Soviet republic.”

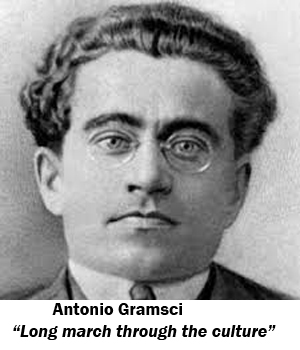

American cultural commentator Linda Kimball has described how two Marxist theorists, Antonio Gramsci of Italy and Georg Lukács of Hungary, “concluded that the Christianized West was the obstacle standing in the way of a communist new world order.”

Gramsci, in particular, wrestled with the question of why workers in the West weren’t rising up to cast out the ruling class, as Marx had predicted. According to Linda Kimball, he concluded that Christianity had “corrupted the working class” and that

… the West would have to be de-Christianized … by means of a ‘long march through the culture’… starting with the traditional family and completely engulfing churches, schools, media, entertainment, civic organizations, literature, science, and [the presentation (and revision) of] history.[iv]

Gramsci believed that as society’s morals were softened, its political and economic foundation would be more easily smashed and restructured.

In 1923 Lukács established the Institution for Marxism in Frankfurt – later known as the Frankfurt School. Lukács said:

I saw the revolutionary destruction of society as the one and only solution. A worldwide overturning of values cannot take place without the annihilation of the old values and the creation of new ones by the revolutionaries.[v]

After the Nazis came to power, many members of the “Frankfurt School,” such as Herbert Marcuse, Eric Fromm, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Wilhelm Reich fled to the United States, where they ultimately found their way into professorships at various elite universities including Berkeley, Columbia and Princeton. In the context of American culture, “the long march through the institutions” meant, in the words of Herbert Marcuse, “working against the established institutions while working in them.”[vi]

The Frankfurt School’s studies combined Marxist analysis with Freudian psychoanalysis to form the basis of what became known as “Critical Theory” – the destructive criticism of Western culture, including Christianity, capitalism, authority, the family, patriarchy, morality, tradition, sexual restraint, loyalty, patriotism, nationalism, ethnocentrism and conservatism.

Critical Theory repeats over and over a mantra of alleged Western evils: racism, sexism, colonialism, nationalism, homophobia, fascism, xenophobia, imperialism and, of course, religious bigotry (only applied to Christianity).

In 1950, Theodor Adorno of the Frankfurt School proposed the idea of the “authoritarian personality” – claiming that

…Christianity, capitalism, and the traditional family create a character prone to racism and fascism. Thus, anyone who upholds … traditional moral values and institutions is both racist and fascist … [and] everyone raised in the traditions of God, family, patriotism … or free markets is in need of psychological help.[vii]

The Frankfurt School members were frustrated at the persistent lack of interest in revolt by the Western working class. Herbert Marcuse asked the question: Who could substitute for the working class as the agent of revolution?

His answer was: marginalized groups, including black militants, feminists, homosexual militants, the asocial, the alienated and third world revolutionaries represented by the mass murderer, Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

Cultural terrorism – now called political correctness – was to be waged against white, Christian, capitalist, heterosexual males.

So victim groups were to be defended: blacks, women, and now Muslims, all alleged victims of “racism “and “genocide.” More recently, the environment was added (allegedly raped by white capitalists).

Marcuse’s book, Eros and Civilization (1955), promoted free love and the pleasure principle – giving rise to the mantra of the late 1960s onward of “Make love, not war” and “If it feels good, do it.” This, in turn, led to the drug counterculture of the 1970s – “turn on, tune in, drop out.” This is very subversive of traditional values including work ethic and the pursuit of excellence. These victim groups are the basis of gay studies, black studies, women’s studies, peace and conflict studies, and so on, departments now infesting universities, along with the “Green Left.” None of these departments encourages genuine critical thought: they peddle only a one-sided agenda of destructive pessimism about Western culture.

Marcuse cautioned his disciples not to be so foolish as to afford the courtesy of free speech to their opponents.

“Certain things cannot be said, certain ideas cannot be expressed, certain policies cannot be proposed, certain behavior cannot be permitted without making tolerance an instrument for the continuation of servitude,” he wrote.

Tolerance is the totem of our age, a bumper sticker of virtue. Yet hidden in its many meanings is the doublespeak of defining what will be taboo. It is now considered tolerant to demand silence from nonconformists.

Cultural Marxism now riddles the institutions of Western society – universities and the public media in particular. Its tactic of political correctness – linguistic fascism – now intimidates and suffocates much of the public discourse. It afflicts the major political parties, not only the Left.

Although the Frankfurt School gradually became autonomous, it continued to receive Soviet support and encouragement. Communist bookstores in Western countries in those days were full of books promoting gay and lesbian rights, land rights, feminism and the rights of minority groups such as America’s blacks and Hispanics. The books, together with Soviet financial and organizational support, spawned activist groups, all with a common pro-communist, anti-American and anti-establishment theme.

Saul Alinsky

While the influence of Marcuse and the Frankfurt School and Marxists like Gramsci was greatest in intellectual circles in a strategic sense, Saul Alinsky arrived on the scene in Chicago in the 1930s with the tactical tools for the foot soldiers of social and political revolution – the community organizers and non-academic labor and single-issue activists.

Alinsky had a certain charm and appeal to wealthy funders, and had no trouble raising considerable sums to establish the Industrial Areas Foundation in Chicago. The foundation was established with money from department store mogul Marshall Field and Sears, Roebuck & Company heiress Adele Rosenwald Levy, as well as Gardiner Howland Shaw, an assistant secretary of state in Franklin Roosevelt’s administration.

Alinsky also had other benefactors in Washington and on Wall Street. Eugene Meyer, former chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1930 to 1933, bought The Washington Post at a bankruptcy sale in 1933 for $825,000. During the difficult years of the Depression that followed, the Post carried stories that legitimized Saul Alinsky and his ideas.

Alinsky’s tactics had more in common with Gramsci and Marcuse than the revolutionary and violent approaches of Russian Marxists Lenin and Stalin. Alinsky, too, believed in gradualism and the subversion of the system through infiltration rather than confrontation and revolution.

Alinsky’s handbook, Rules for Radicals, first published in 1971,[viii] sets out the path for community organizers to achieve the aims of Gramsci and followers of the Frankfurt School.

Known as the godfather of “community organizing” – a term that serves as a euphemism for fomenting public anger, political hatred, and in some cases, violence – he laid out a set of basic tactics designed to help radical activists and politicians destroy their enemies while gaining power for themselves.

Such radicals, said Alinsky,

“must first rub raw the resentments of the people” by selecting a particular political adversary and “publicly attack[ing]” him as a “dangerous enemy” of the people.[ix]

“Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it,” Alinsky taught,[x] asserting that the primary task of radical activists and political figures is to cultivate in people’s hearts a visceral emotional revulsion to the mere sight of the enemy’s face, or to the mere sound of the enemy’s voice.

Alinsky taught that in order to most effectively cast themselves as defenders of moral principles and human decency, radical activists and political figures should take great pains to react dramatically – with highly exaggerated displays of “shock, horror, and moral outrage” – whenever their targeted enemy misspeaks or errs in any way.[xi]

Alinsky also emphasized the need for activists and political radicals to convince their followers that the chasm between themselves and the enemy is vast and unbridgeable. “Before men can act,” he wrote, “an issue must be polarized. Men will act when they are convinced their cause is 100 percent on the side of the angels, and that the opposition are 100 percent on the side of the devil.”[xii]

One way in which radicals and their disciples can broadcast their preparedness for this possibility, Alinsky taught, is by staging loud, defiant, massive protest rallies expressing deep rage against, and contempt for, their political adversary. Such demonstrations – like the so-called “Women’s Marches” – can give onlookers the impression that a mass movement is preparing to shift into an even higher gear. Alinsky advised:

“Wherever possible, go outside the experience of the enemy. Here you want to cause confusion, fear, and retreat.”[xiii]

Reading the above rules, it is abundantly clear the Alinksy disciples have chosen President Trump as the target for their hysterical, unrelenting attacks. The Alinskyites are following the rules to the letter.

Alinsky succeeded in what would be a crowning achievement: the recruitment of young, idealistic radicals – Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama – who would go on to climb to the top of the Democratic Party and hold some of the highest offices in the world. Hillary Clinton wrote her senior thesis at Wellesley College in 1969 on Alinsky’s methods and remained a friend of Alinsky until his death in 1972. A decade later, Barack Obama was trained in the methods and Rules for Radicals in the Alinsky-founded Industrial Areas Foundation in Chicago.

The Beats

Some of the first people to be influenced by the Frankfurt School were a group of people who were to become known as the Beats. Representative figures of the Beat Generation were poet Allen Ginsberg and the novelist William S. Burroughs.

Roger Kimball has noted:

The Beats are crucial to an understanding of America’s cultural revolution not least because of their lives, their proclamations and their “work.” Their programmatic anti-Americanism, their avid celebration of drug abuse, their squalid, promiscuous sex lives, their pseudo-spirituality, their attack on rationality and their degradation of intellectual standards, their aggressive narcissism, set the stage for their successors in the cultural revolution.[xiv]

As the 1950s wore on, anti-Americanism became a necessary badge of authenticity for writers and intellectuals; more and more, the cultural establishment demanded the pose of anti-establishment animus.

Soviet agent Susan Sontag

One of the key figures in the cultural revolution was Susan Sontag. From the moment she burst upon the scene in the early 1960s, with her essays, “Against Interpretation” and “Notes on ‘Camp’,” and her declaration that “the white race is the cancer of human history”[xv] (italics are Sontag’s), she has been a model for radicalism.

Soviet agents of influence, like Susan Sontag, invaded the academic and intellectual environment with virulent anti-Americanism, helping spread cultural Marxism.

Sontag made a number of visits to communist countries. In Cuba, 1969, she declared, “America is a cancerous society.”

Few people have managed to combine the naïve idealization of foreign tyranny with a violent hatred of their own country to such deplorable effect as Sontag.

Sontag was a professor, critic, novelist, playwright, filmmaker and full-time political radical. Sontag was born Susan Rosenblatt, in New York City, to Jewish parents. She graduated from the University of Chicago with a Bachelor of Arts degree.

There were two significant episodes in her early life. The Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse lived with Sontag and her husband Philip Rieff for a year while working on his 1955 book, Eros and Civilization.[xvi]

In 1957 she transferred to the University of Paris where she socialized with expatriate artists and French Marxist intellectuals and academics.

Sontag also travelled to Cuba and North Vietnam in 1968 and China in 1973.

Following her visit to Cuba, she wrote: “the Cuban revolution is astonishingly free of repressions and bureaucratization.”

Similarly, following her visit to Vietnam in 1968, courtesy of the North Vietnamese government, she wrote:

“They genuinely care about the welfare of hundreds of captured American pilots and give them bigger rations than the Vietnamese population gets.”

Shortly before her trip to Vietnam, she wrote:

“A small nation of handsome people is being brutally and self-righteously slaughtered by the richest and most grotesquely over-armed, most powerful country in the world. America has become a criminal, sinister country – swollen with priggishness, numbed by affluence, bemused by monstrous conceit that it has the mandate to dispose of the destiny of the world.”[xvii]

In her 1967 essay, “What’s happening in America?”, Sontag tells readers that what America “deserves” is to have its wealth “taken away” by the “Third World” and, as mentioned previously, that “the white race is the cancer of human history.”[xviii]

No account of America’s cultural revolution would be complete without some discussion of the Vietnam War. More than any other event, it legitimized anti-Americanism and helped insinuate radical feeling into the mainstream of cultural life.

A key point in the cultural revolution occurred with the capitulation of certain key university presidents who helped to sanction (and therefore recommend to society at large) a whole set of radical attitudes, not only about the war and America’s role in it, but also about art, education and morality.

Roger Kimball writes:

It has been in the life of art and the life of mind, however, that the counterculture has had its most devastating effects. To an extent that would have been difficult to imagine thirty years ago, art and education have become handmaidens of political radicalism. Standards in both have plummeted.

Colleges and universities have given themselves up to an uneasy mixture of politically correct causes and the rebarbative rhetoric of deconstruction, post-structuralism and “cultural studies.”

The story of what has happened to our institutions of high culture since the Sixties is a story of almost uninterrupted degradation and pandering to forces inimical to culture.[xix]

Radicals capture American universities

The universities were the scenes of the most violent confrontations and abject betrayals of principle. They provided the perfect breeding ground for the anti-American radicalism extolled by figures like Sontag.

When the dust had cleared, the universities were still standing, their faculties and departments intact. But the long march of the cultural revolution had largely transformed them from bastions of the Western intellectual tradition into repositories of politically-correct sentiment in which intellectual standards had collapsed. It was a capitulation to radicalism which had the goal of destroying an intellectual tradition, and ultimately, a way of life.

America was totally unprepared for the suddenness of the capture of the universities. The president of Boston University, John Silber, noted in 1974, “From the first seizure of a campus building at the University of California at Berkeley on December 2, 1964, this conversion took just four years.”[xx]

The confrontation at Berkley produced endless rallies, marches, protests and vigils, some of which involved upwards of 7,000 people, bringing the university to the edge of collapse.

The Cornell surrender

The collapse of authority at Cornell University was symptomatic of the revolution on American campuses.

The liberal-minded president of Cornell, James A. Perkins, came to the job brimming with good intentions. One of Perkins’ first projects was to recruit black students whose scores were well below the average of Cornell’s entering class.

The number of black students rapidly rose from 25 to about 250. Seeking solidarity, they banded together to form an Afro-American Society. They then began issuing various demands: including for separate black-only living quarters and for Afro-American studies programs, again for blacks only. And, finally, they demanded that the university create an autonomous degree-granting college-within-a-college for the exclusive use of black students, the aim of which was to “create the tools necessary for the formation of a black nation.”

After a certain amount of equivocation, Perkins acceded to the demands.

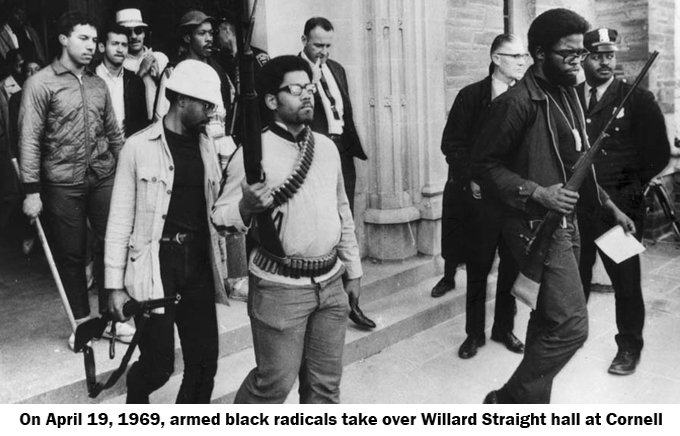

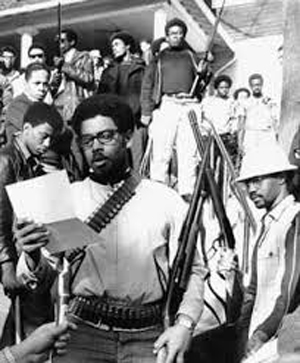

Armed black students take over Cornell University

In 1968, black students at Cornell charged a visiting professor of economics with racism because he had dared to judge African nations by a “Western” standard of development. The administration required an apology from the professor: he complied, but the students were not satisfied and took possession of the economics department, holding the chairman, and his secretary, prisoner for 18 hours. The students were never punished.

The following months saw an escalating pattern of “non-negotiable demands,” vandalism and violence. Buildings were occupied, hostages taken and college property destroyed.

These matters became a crisis in the spring of 1969. On Saturday, April 19, during parents’ weekend, some 100 black students walked into Willard Straight Hall shortly before 6:00 am and gave the occupants 10 minutes to leave. Doors were broken down with crowbars when occupants were slow in responding. Some 30 parents and 40 college employees were forcibly ejected from the building.

University officials then stood by passively while the black students armed themselves with knives, rifles and ammunition. With militants from the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) forming a protective guard outside, the black students settled down for what turned out to be a 35-hour occupation of the building.

When some white students broke into the building later in the day, a scuffle broke out that sent several students to the infirmary. One black student shouted out the warning that “if any more whites come in, you’re gonna die here.”

A hundred sheriff’s deputies, some armed with tear gas and shotguns, had gathered in downtown Ithaca, ready to move to the campus. The tension in the gym was fierce, and so was the language of the speakers.

Black leader, Tom Jones, declared:

“In the past it has been all the black people who have done all the dying. Now the time has come when the pigs are going to die, too. We are moving tonight. Cornell has until 9 o’clock to live. It is now three minutes past eight.”

Cornell did not die at 9 o’clock that night. The faculty rescinded its reprimands, and the university survived.

When the administration caved into the demands of occupiers, the black students vacated the building victorious, clutching rifles and ammunition belts, their clenched fists raised in defiance.

In a sign of America’s cultural and moral decay, Jones and his gang of armed thugs were never brought to justice. Instead, Cornell later rewarded Jones by making him a trustee of the university. He went on to become president of TIAA-CREF, the world’s largest pension fund.

The grotesque events at Cornell were bad enough on their own, but their real significance was as a prelude to similar depredations elsewhere.

By capitulating, Perkins did a great deal to politicize the university and undermine its claims to intellectual independence.

Constitutional law and political philosophy professor Walter Berns, who taught at Cornell during the upheaval, pointed out that:

… [Perkins] had made it easier for those who came after him to surrender to students armed only with epithets (“racists,” “sexists,” “elitists,” “homophobes”); by inaugurating a black studies program, Perkins paved the way for Latino studies programs, women’s studies programs and multicultural studies programs; by failing to support a professor’s freedom to teach, he paved the way for speech codes and political correctness; and of course he pioneered the practice of affirmative action admissions and hiring.

Cornell was the prototype of the university as we know it today, having jettisoned every vestige of academic integrity.[xxi]

Berns was part of a small group of professors who spoke out against the radicals. Once the student takeover was settled in favour of the protesters, and after receiving personal threats, Berns resigned from Cornell and took up a position at the University of Toronto.

The cultural climate of America, including that of higher education, was transformed by a blitzkrieg of radical activism.

Quickly introduced were Afro-American studies programs, women’s studies, gay studies, transgender studies, affirmative action and even entire colleges set up for supposedly victimized minorities.

The really toxic effects of the cultural revolution only started to be felt latterly, when the revolution is said to be “over.” By then, its characteristic attitudes have been so widely incorporated into the mainstream of life that they are taken for granted, and have become the norm, the way of life.

Some of the gun-toting activists, bomb-makers and their acolytes are now journalism professors, judges, editors and legislators.

Although described by various authors as a cultural revolution, it was more than that: it was an insurrection. Armed thugs invaded university buildings and held hostages. Alleged spies were murdered. Hundreds of bombs were detonated. According to a story in the Los Angeles Times: “In California alone, 20 explosions a week rocked the state during the summer of 1970.”[xxii]

Within weeks of the Cornell takeover, student uprisings occurred on the campuses of Dartmouth College and Princeton, Tulane and Howard universities.

The insurgents were successful in capturing not territory, but the intellectual, cultural and moral foundations of America, and subsequently the English-speaking world.

The university as a bastion of reasoned argument, thoughtful debate and academic freedom was gone forever.

Western universities captured by neo-Marxists

Today, the capture of Western universities by neo-Marxism is complete.

In universities across the Western world, students training to become teachers are commonly taught critical theory or post-colonialism as part of arts degrees in education. Both subjects inculcate in students deep hostility towards the Western world, its culture, creed and citizens. They were inspired by neo-Marxism, whose forefather, Herbert Marcuse, was a key figure leading the revolution against Western civilization in universities, as well as the rise of radical minority groups to censor non-leftist thought in public life.

The most celebrated educational theorist in teaching or pedagogy, Paulo Freire, a Brazilian, was inspired by neo-Marxism. The foreword to his seminal work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed,[xxiii] lists Marcuse as a key influence. Freire founded critical pedagogy, a theory that denounces the primary purpose of education, to teach students how to think, and replaces it with activist education where students learn what to think. Freire’s technique reduces the teacher to the level of a student and both are instructed to become revolutionaries against the oppressor class, whose chief feature appears to be anything that resembles worldly success. Freire regards education not as the pursuit of objective truth but as an instrument of “cultural revolution.”

Like Freire, the chief architect of post-colonialism, Frantz Fanon, an Afro-Carribean psychiatrist and philosopher, believed education should be used to foment leftist revolution. He celebrated Islamism as a revolutionary activity, advocating a combination of militant socialism and neo-Marxist minority politics to provoke war against the West. Fanon sought not only the end of colonialism but the destruction of Western civilization by a sustained attack on its core values. In his 1961 book, The Wretched of the Earth, he dreamt of a revolutionary climax where: “All the Mediterranean values – the triumph of the human individual, of clarity, and of beauty – become lifeless… Individualism is the first to disappear.”[xxiv]

Marxist academics, journalists and authors are re-writing history, undermining the history of Western civilization to emphasize the evils of slavery, the treatment of indigenous and oppressed colonial populations and the phony evil, “racism.”

Universities, once the great bastions of Western intellectual discourse and discovery, have become fortresses of rigid left-wing orthodoxy that brook no dissenting views. Campuses today resemble the communist re-education camps of North Korea and North Vietnam, except that the indoctrination process is more subtle.

The revolution overturned the Western intellectual and cultural tradition in universities and replaced it with emotionalism, neo-Marxist minority rights and militant mob rule. Its outward expression is a codified regime of political correctness directed against the PC Left’s principal target: the white, heterosexual male of conservative and/or Christian persuasion.

Once it may have been possible to turn back this tide of neo-Marxism and its attendant disdain, and even hatred of Western culture.

Sadly, now it may be too late.

Each year, in the Western world, hundreds of thousands of university graduates set forth to enter the workforce, many carrying with them their baggage of cultural Marxism from years of women’s studies, minorities studies, transgender studies, environment and climate studies.

These neo-Marxists go on to become journalists, editors, academics, social workers, entertainers, community leaders, lawyers and judges. Some have started up tech companies that become monopolistic behemoths such as Facebook, Google and Twitter, where they use the power of their social media platforms to slowly but inexorably strangle free speech of the conservative variety.

There is a considerable amount of pent-up anger in certain segments of society, some generated by Marxist indoctrination at university about the supposed evils of Western civilization, including colonialism, capitalism, white supremacy, racism and suppression of minorities and some generated within minority groups following years of “oppression” propaganda and perceived mistreatment.

It doesn’t take much for this anger to flare into violence, arson and even looting as we have seen with the Minneapolis riots.

Chapter 6: The Long March through the Institutions – references

Chapter 6: The Long March through the Institutions – references

[i] Roger Kimball, The Long March: How the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s Changed America (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2000), p. 5.

[ii] David Frum, How We Got Here: The 70’s: The Decade That Brought You Modern Life (For Better or Worse) (New York: Basic Books, 2000), p. xxiv.

[iii] Paul Oskar Kristeller, A Life of Learning (New York: American Council of Learned Societies, 1990): Charles Homer Haskins Lecture, April 26, 1990, ACLS Occasional Paper, No. 12, p. 14.

URL: www.acls.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/OP/Haskins/1990_PaulOskarKristeller.pdf

[iv] Linda Kimball, “Cultural Marxism”, American Thinker, February 15, 2007.

URL: www.americanthinker.com/articles/2007/02/cultural_marxism.html

[v] Georg Lukács, quoted in Robin Phillips, “Liquidating Western civilization: the legacy of the Frankfurt School”, Centurean2’s Weblog (UK), September 26, 2011.

URL: https://centurean2.wordpress.com/2011/09/26/liquidating-western-civilization-the-legacy-of-the-frankfurt-school/

[vi] Herbert Marcuse, Counterrevolution and Revolt (Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 1972), p. 55.

[vii] Linda Kimball, “Cultural Marxism”, op. cit.

[viii] Saul D. Alinsky, Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals [1971] (New York: Vintage Books, 1989).

[ix] Ibid., p. 100.

[x] Ibid., pp. 130-131.

[xi] Ibid., p. 130.

[xii] Ibid., p. 78.

[xiii] Ibid., p. 127.

[xiv] Kimball, The Long March, op. cit., p. 27.

[xv] Susan Sontag, “What’s happening in America? (A symposium)”, Partisan Review (Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey), Vol. 34, No. 1, Winter 1967, pp. 57-58.

[xvi] Herbert Marcuse, Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud (Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 1955).

[xvii] Kimball, The Long March, op. cit., pp. 95-96.

See also: Paul Hollander, Travels of Western Intellectuals to the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981).

[xviii] Sontag, “What’s happening in America?”, op. cit.

[xix] Kimball, The Long March, op. cit., p. 32.

[xx] John R. Silber, “Poisoning the wells of academe”, Encounter (New York), Vol. 43, No. 2, August 1974, p. 30.

URL: www.unz.org/Pub/Encounter-1974aug-00030?View=PDF

[xxi] Walter Berns, “The assault on the universities: then and now”, in Stephen Macedo, ed., Reassessing the Sixties: Debating the Political and Cultural Legacy (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997), p. 163.

[xxii] Nina J. Easton, “America the enemy”, Los Angeles Times, June 18, 1995: magazine section.

URL: http://articles.latimes.com/1995-06-18/magazine/tm-14239_1_political-violence

[xxiii] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 1970).

[xxiv] Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth [1961], English trans. (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1963), p. 46.